In Part 1 of this 2-part series, I provide an overview of pain tolerance, factors that affect pain tolerance, and assessment of clinical pain. Today’s Part 2 focuses on a detailed discussion of several guided imagery and healing techniques, such as “Mind Controlled Analgesia,” positive and negative imagery, and the importance of relaxation. Readers are encouraged to first review Part 1 to better understand the topics explored in this second and final discussion of pain and guided imagery.

Guided Imagery and Healing

Mental images – formed long before we learn to understand and use words – lie at the core of who we think we are, what we believe the world is like, what we feel we deserve, and how motivated we are to take care of ourselves. They strongly influence our beliefs and attitudes about how we fall ill, what might help us get better, and whether or not any medical and/or psychological interventions will be effective or even helpful. For these reasons, learning how to guide our patients’ imagery can be an enormously powerful tool for modern pain therapists.

A mental image can be defined as a thought with sensory qualities. It is something we mentally see, hear, taste, smell, touch, or feel. The term “guided imagery” refers to a wide variety of mind/body techniques, including simple visualization and direct suggestion using imagery, metaphor and story-telling, fantasy exploration, game playing, dream interpretation, drawing, and “active imagination” where elements of the unconscious are invited to appear as images that can communicate with the conscious mind.

Once considered “mumbo-jumbo,” or at best, an “alternative” or “complementary” approach, guided imagery is finding widespread scientific [9] and public [10] acceptance, and nearly ever bookstore now offers guided imagery self-help CDs or DVDs [11].

Research on the omnipresent placebo effect, the standard to which we compare all other modalities (and find relatively few more powerful), has provided some of the strongest evidence for the power of the imagination and positive expectant faith in healing.

If people can derive not only symptomatic relief, but actual physiologic healing in response to treatments that primarily work through beliefs and attitudes about an imagined reality, then learning how to better mobilize and amplify this phenomenon in a purposeful, conscious way becomes an important, if not critical, area of investigation for modern medicine.

Imagery Has Physiological Consequences

In the absence of competing sensory cues, all the systems in the body respond to imagery as they would to a genuine external experience. For example, take a moment to imagine that you have a big, fresh, juicy yellow lemon in your hand, just plucked this morning. Allow an image of this lemon to form in your mind’s eye so you can fully sense its heaviness and smell its fresh, lemony tartness. Now, imagine taking a knife and carefully cutting out a thick, juicy section from the lemon. In a moment, I’d like you to imagine taking a big bite of the lemon slice, and as you do, feel that sour, tart lemon juice explode in your mouth, saturating every taste bud so fully that your tongue begins to curl as your lips pucker up…

To the extent you were able to imagine this vividly, even as you read it, the image probably produced some salivation, for the autonomic nervous system easily understands and responds to the language of imagery.

Here is the crux of the matter: If imagining a lemon makes you salivate, what happens when you imagine that you are a hopeless, helpless victim of never-ending pain? Doesn’t it tell your body’s intrinsic healing systems to stop and give up?

Imagery, Attention, and Worrying

Some people feel that they have little ability to create images in their minds, but everyone can cultivate this talent to an amazingly high degree. In fact, the most common way that people use imagery is by worrying. What we worry about is never happening in the real world, only in our imagination. We regret the past, which has already happened, or become fearful about the future, which is a total fantasy since it has not happened yet.

People in pain worry all the time. They worry that their pain will never end and that they will remain helplessly immobilized by something they cannot control and cannot endure. As a result, they usually have little difficulty describing an image of their pain at its very worst. I’ve often heard phrases like, “a swarm of fire ants are chewing on the nerve”, or “a gigantic elephant is sitting on my chest.” These are familiar and powerful images that immediately come to mind as soon as the first symptoms of pain emerge.

There is an old saying that “whatever you give your attention to grows,” whether it is your garden, your children, your worries and fears, or your experience of pain. Because patients tend to worry about pain at its worst much of the time, this image gets a lot of attention. As a result, it grows very large and soon becomes a major focus of the patient’s life experience.

These negative images can also become self-fulfilling prophecies, for they have the power to create their own reality in the body, just as thinking of a lemon can make you salivate. If a patient experiences pain as “a sizzling hot poker that is constantly being stabbed into my knee”, or as “a lion gnawing on my back, tearing deeper into my nerves with every bite”, such images can have profound physiological effects that can increase the experience of suffering and interfere with the body’s natural pain relieving abilities [12].

Negative Imagery as a Habit

Over time, thinking about the image of pain at its worst becomes habitual, and despite reassurance from health care providers, family, and friends, patients tend to remain constantly anxious that it will occur again. While it may be counterintentional to focus so much attention on this horrible image, many patients feel that they are unable to stop thinking about it, just as they were unable to quit smoking or lose weight. Painful negative imagery has become a habitual way of thinking.

How do you best break an old habit? By learning a new one that is incompatible with the old one, and then by thoroughly reinforcing the new habit until it replaces the old one. In other words, to stop a patient’s habitual way of thinking that pain will always be unbearable, we need to create a new image of pain that is incompatible with the old one, and then reinforce it by giving it as much attention as possible.

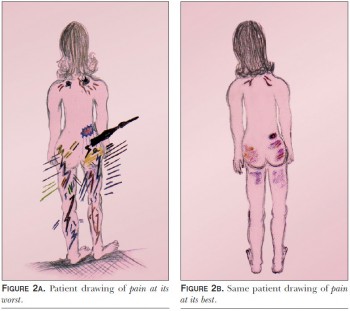

A Picture of Pain At Its BestIn addition to a drawing picture of their pain at its worst, I invite patients to get in touch with their pain at its best by using the suggestions in Table 2.

Once this image comes to mind, I ask the patient to draw a picture that represents their pain at its best. If a patient has difficulty creating a positive image of pain, it is usually because they are highly anxious and so uncomfortable that they do not want to acknowledge that pain can ever be “at its best.” In such cases, it is very helpful to teach them basic relaxation skills using other guided imagery techniques such as Conditioned Relaxation [13].

The Importance of Relaxation

While anxiety, fear, stress, and emotional upset do not usually cause pain, these emotions can greatly amplify the pain signal and/or significantly reduce tolerance when they continue unabated over time.

When a patient becomes stressed and afraid that their pain is going to get out of control, the pain signal becomes increased which makes pain less tolerable and more difficult to handle. Teaching patients how to relax can help to calm their nervous system and often reduces or eliminates the amplification effects of anxiety and stress.

We usually begin by having patients sit down or lie down, close their eyes, and focus all of their attention on their breathing. Once they do, we ask them to make their breathing a little bit slower, deeper, quieter and more regular. This alone can be highly effective in reducing stress and anxiety. A simple relaxation exercise is included in Table 3.

After focusing on their breathing, we ask them to systematically scan each part of their body and to notice any parts that still have any tension, tightness, pain, or discomfort. If they do, we ask them to use their breath to blow away any discomfort as they exhale, and as they inhale, to bring healing, nourishing oxygen to every cell in the area of discomfort.Next, we ask them to bring to mind a place that is very beautiful, peaceful, safe and comfortable – a place that they love to think of in their imagination. It might be a real place they’ve actually visited, or a place they’ve totally invented. Once there, we ask them to notice what they see, hear and smell, what the temperature is like, and what time of day it is.

As they pay attention and focus on different sensory cues, their body’s regulatory systems respond as if they are actually in such a place. This shifts the autonomic nervous system into more parasympathetic activation, generating the relaxation response.

Thanks to recent studies with functional MRIs, we now know that when people imagine that they see trees, flowers and a beautiful blue sky, they actually activate the occipital areas of their brains. When they imagine hearing sounds, they activate the temporal lobes of their brains. As they imagine the different senses, they actually activate different parts of the brain that normally process those senses.

In other words, when the brain concludes that “This looks like a beautiful, peaceful place, it feels like it, it sounds like, and it smells like it,” the entire body responds by becoming more relaxed, just as if it were there.

Mind-Controlled Analgesia

This guided imagery technique can be used once patients have drawn their pictures of pain at its worst and best (see Figures 2a and 2b, respectively). Mind Controlled Analgesia (MCA) is designed to elevate pain tolerance by transforming the first image into the second.

After inducing relaxation as discussed above, typical suggestions for MCA are shown in Table 4. After learning MCA, patients are reminded that every time that they start to bring the picture of pain at its worst to mind, they need to immediately transform it into the picture of pain at its best, remembering that they have the ability to tolerate their pain, and it is time to put that ability into practice.

Problem SolvingSome people think they cannot draw pictures in their imagination because they “don’t see anything.” That is fine because imagination is not necessarily what you see, but what you experience. Can you recall the song Jingle Bells? Do you remember how it goes? Are you “hearing” Jingle Bells or just imagining it? In the same way, it does not matter whether you “see” anything or not if you can experience it, like the taste of an imaginary lemon.

If your patient reports that their mind wanders or they find it difficult to concentrate, make sure they’ve removed anything distracting from their environment and encourage them to stay with it. Tell them not to be alarmed or frustrated, and to simply imagine that any distracting thoughts are like passing butterflies, flittering off into the distance. Suggest that they let them go and return their attention to remembering that they know how to tolerate pain.

Resources

If your patients are still having difficulty mastering Mind Controlled Analgesia, I recommend that you refer them to a Certified Interactive Imagery Guide (SM). These are licensed clinicians and health educators who have been rigorously trained and then certified by the Academy for Guided Imagery. More information and a free referral directory can be found online at www.AcadGI.com.

Patients can also benefit by listening to pre-recording CDs that contain “over the counter” strength guided imagery exercises. While not as personalized as working with a certified imagery guide, they provide an inexpensive way for patients to learn on their own. When using CDs, its important for the voice of the guide to be pleasing to the listener, and that the pacing (or speed) of the imagery is comfortable and relaxing. If the suggestions are offered too quickly, the experience can become frustrating since the images do not have enough time to fully develop. And if it moves too slowly, the experience becomes very boring and listeners then doze off to sleep. CDs created by the author are available at www.acadgi.com/imagerystore.

The Academy also trains health care providers who are interested in incorporating guided imagery into their practices. The introductory program requires only thirteen hours of home study, after which they are able to begin utilizing the basic techniques that are suitable for many acute and chronic pain problems.

David E. Bresler, PhD, LAc, DiplAc (NCCAOM)

Practical Pain Management is a monthly journal that contains tutorial articles designed to help diagnose and treat various aspects of pain. This publication is sent free of charge to medical practitioners in the United States.

Citation / Material adapted (with permission) from:

Bresler, D. (2010). Raising pain tolerance using guided imagery. Practical Pain Management, July/August, 10(6), 25-31.

References

1. Woodrow KM, Friedman GD, Siegelaub AB, and Collen MF. Pain Tolerance: Differences According to Age, Sex, and Race. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1972. 34(6): 548-556.

2. Lowery D, Fillingim RB, and Wright RA. Sex Differences and Incentive Effects on Perceptual and Cardiovascular Responses to Cold Pressor Pain.” Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003. 65: 284-291.

3. Brown JL, Sheffield D, Leary MR, and Robinson ME. Social Support and Experimental Pain. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003. 65: 276-283.

4. Kalat JW. Biological Psychology, 9th edition. 2007. p. 212.

5. Ikeda H, Heinke B, Ruscheweyh R, and Sandkùhler J. Synaptic plasticity in spinal lamina 1 projection neurons that mediate hyperalgesia. Science. 2003. 299: 1237-1240.

6. Excerpted from Bresler DE. Mind Controlled Analgesia. LA: Imagery Resources. 2008. Available from www.acadgi.com/imagery store.

7. Bresler DE. Free Yourself From Pain. Simon and Schuster. NY. 1969. Currently available from www.acadgi.com/imagery store.

8. Bresler DE. The Pain Relationship. Pract Pain Manag. Jan/Feb 2001. 1(1): 10-11.

9. Astin JA, Shapiro SI, Eisenberg DM, Forys KL. Mind-body medicine: state of the science, implications for practice. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004. 165(2): 131-147.

10. Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SI, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998. 280(18): 1569-1575.

11. An excellent selection of pre-recorded guided imagery CDs can be found by visiting the Imagery Store at www.acadgi.com.

12. Bresler DE. Physiological Consequences of Guided Imagery. Pract Pain Manag. Sept/Oct 2005. 5(6): 63-67.

13. Bresler DE. Conditioned Relaxation. LA: Imagery Resources. 2009. Available from www.acadgi.com/imagerystore.

No comments yet.